Top Brand LLC v. Cozy Comfort Company LLC, Appeal No. 2024-2191 (Fed. Cir. July 17, 2025)

In this week’s Case of the Week, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that prosecution history disclaimer applies to design patents. The Court also reversed a jury verdict awarding $3.08 million in damages to Cozy Comfort for trademark infringement. The patent at issue concerns oversized hooded sweatshirts.

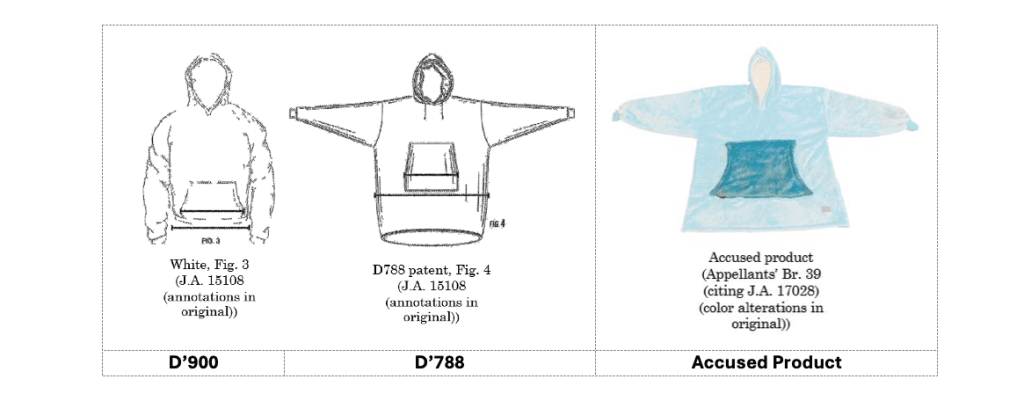

Cozy Comfort owns the D’788 patent for an “oversized wearable blanket.” The Examiner initially rejected the application for the D’788 patent as anticipated by a separate patent: the D’900 patent. To overcome this rejection, Cozy Comfort agreed that certain aspects of its design differed from the design in the D’900 patent and disclaimed the significance of specific features such as the shape and placement of the pocket located at the front of the torso and shape of the bottom hem line. Cozy Comfort also owns two registered trademarks for “THE COMFY” mark for use in connection with blanket throws and online retail service featuring blanket throws. In 2020, Top Brand sought a declaratory judgment of noninfringement and invalidity after Cozy Comfort alleged that Top Brand’s hooded sweatshirts and wearable blankets infringed its D’788 patent.

During trial, Top Brand requested the district court provide a detailed verbal construction limiting the construction of the D’788 patent based on the statements made by Cozy Comfort during prosecution of the application. Instead, the jury was instructed to “determine whether or not there is infringement by comparing the accused products to the design defined in the patent.” The jury returned a verdict that Top Brand infringed the D’788 patent, awarding $15.4 million in damages. In addition, the jury awarded Cozy Comfort $3.08 million in damages for trademark infringement of Cozy Comfort’s “THE COMFY” marks. Top Brand also filed a motion for judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) for the design patent and trademark infringement, which was denied.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit first considered whether the district court erred in declining to construe the D’788 patent as limited by prosecution history disclaimer. The Federal Circuit rejected Cozy Comfort’s argument that the doctrine of prosecution history disclaimer does not apply to design patents, finding that the scope of a design patent may be limited by claim amendments or arguments made to the PTO. The Court relied on its decision in Pacific Coast Marine Wind-shields Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC, 739 F.3d 694 (Fed. Cir. 2014), where a claim was limited by an applicant’s amendment in response to a restriction requirement issued by an examiner. In that case, the Federal Circuit held the applicant narrowed the scope of its original application, thereby surrendering subject matter. The Court also noted that their approach is supported by their decision in Egyptian Goddess Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc), where the Court held that the trial court can guide the jury by “assessing and describing the effect of any representations that may have been made in the course of the prosecution history” among a number of other issues that affect the scope of a claim.

Following this reasoning, the Federal Circuit ruled that the district court erred in denying Top Brand’s JMOL because, under the proper construction of the D’788 patent, no reasonable jury could find infringement in this case. The Court found that multiple significant aspects of the accused product, including the location and placement of the torso pocket and angle of the bottom hem, were the same ones Cozy Comfort disclaimed during prosecution, and thus could not be relied on to demonstrate similarities between the accused product and Cozy Comfort’s design patent. Further, Cozy Comfort failed to point to features that were not disclaimed in its infringement argument. Nor did Coxy Comfort argue that the overall arrangement of the accused product created an appearance deceptively similar to the D’788 patent. The Court declined to address the issue of validity.

Turning to the issue of trademark infringement, the Federal Circuit also reversed the district court’s denial JMOL for trademark infringement of the registered trademarks for “THE COMFY.” The Court found that the mark “THE COMFY” is entitled to weaker protection because the dominant part of the mark “comfy” is descriptive of blanket throws and rejected Cozy Comfort’s argument that the brief use of the word “comfy” on Top Brand’s website amounted to use of the word as source identifier.

The full opinion can be found here.

By Brittani Gambrell

ALSO THIS WEEK

Colibri Heart Valve LLC v. Medtronic Corevalve, LLC, Appeal No. 2023-2153 (Fed. Cir. July 18, 2025)

This case essentially analyzes two key questions: are a method for implanting a replacement heart valve involving pushing and a similar method involving retraction equivalents for the purpose of determining infringement, and does prosecution history narrowing a claim for both to one only reciting pushing bar a doctrine of equivalents argument?

In this case, Colibri Heart Valve, LLC sued Medtronic Core Valve, LLC a manufacturer of replacement heart valves, in district court for infringement of a claimed method for implanting replacement artificial heart valves. Colibri alleged that Medtronic was inducing surgeons to perform Colibri’s claimed method with Medtronic’s products. Medtronic contended that the accused use of its product involved partial deployment of a valve via a moveable sheath by retracting, not pushing – the patent at issue included no claims expressly reciting deployment by retracting.

At the outset of prosecution of the Colibri patent at issue here, “Method of Controlled Release of Percutaneous Replacement Heart Valve” (U.S. Patent No. 8,900,294), the patent included claims for partial-deployment of a replacement heart valve both via pushing and via retraction. However, during prosecution, Colibri cancelled its claim reciting retraction. As issued, the patent included no claims expressly reciting deployment by retracting. Rather, the ’294 patent was issued only with an independent claim “reciting partial deployment of a replacement heart valve from an outer sheath of a delivery apparatus by pushing.”

In its complaint filed in district court, Colibri claimed that, under the doctrine of equivalents, Medtronic’s method for valve replacement (applying a force to hold a stent in place while retracting a moveable sheath to insert a replacement valve) is equivalent to the claimed partial-deployment method (applying a force to push the stent out of the moveable sheath). The jury agreed, finding that Medtronic had induced infringement and awarded more than $106 million in damages to Colibri. Before and after the verdict, Medtronic sought JMOL on the ground, among others, that Colibri’s doctrine of equivalents claim was barred by prosecution history estoppel. The district court denied the motions.

The Court of Appeals reversed here, concluding that Colibri’s cancellation during prosecution of its claim reciting retraction barred Colibri from asserting infringement under the doctrine of equivalents under the theory that “a combination of applying a pushing force to the pusher member while retracting the moveable sheath (what Medtronic’s device does) is equivalent to, i.e. not substantially different from, “pressing against the pusher member with a force that moves the pusher member outward from the moveable sheath (what [Colibri’s claim] requires.)”

The Court found that Colibri’s cancellation of the claim which recited partial deployment by retraction during prosecution was relevant to what can be claimed as equivalent. “Where the original application once embraced the purported equivalent but the patentee narrowed his claims to obtain the patent or to protect its validity, the patentee cannot assert that he lacked the words to describe the subject matter in question.” The Court relied on Honeywell International Inc. v. Hamilton Sundstrand Corp., 370 F.3d 1131 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (en banc.), reciting its holding in that case that “the cancellation of a prior, broader independent claim may give rise to prosecution history estoppel in relation to a narrower claim…”

The Court determined that Medtronic was entitled to JMOL of noninfringement of the ’294 patent, reversing the district court’s denial of such judgment and mooting the remaining aspects of Medtronic’s appeal (i.e. those relating to invalidity, remaining noninfringement arguments, and damages).

The full opinion can be found here.

By Julia Davis

Shockwave Medical, Inc. v. Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., Appeal Nos. 2023-1864, -1940 (Fed. Cir. July 14, 2025)

In cross-appeals from an inter partes review of Shockwave’s U.S. Patent No. 8,956,371 for treating atherosclerosis, the Federal Circuit purported to clarify the appropriate role of applicant-admitted prior art (“AAPA”) in IPRs. The ’371 patent claims treatment methods using lithotripsy—the use of sonic shockwaves to break up material, as is well-known in the treatment of kidney stones—in combination with an angioplasty balloon catheter that the patent’s specification admitted was well-known in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 311(b), IPRs are limited to challenges based on “patents or printed publications.” The Court had previously held that AAPA references in a challenged patent’s specification are not “patents or printed publications” and thus could not form the basis of a petitioner’s challenge, they could nonetheless be relied on as evidence of the background knowledge of an ordinarily skilled artisan.

Here, Shockwave argued that that Board and challenger CSI had improperly relied on the AAPA concerning angioplasty balloon catheters as a “basis” for invalidation, but the Federal Circuit disagreed. The panel explained that a POSITA’s background knowledge could be used to provide a motivation to combine or even supply missing claim limitations, and found that the Board properly relied on AAPA for such purposes here. In distinguishing its precedent, the Court focused primarily on whether the AAPA had been labeled as a “basis” or as background knowledge in the IPR petition, e.g., “This case is quite different from Qualcomm II, where the petitioner expressly labeled AAPA as a ‘basis’ for its challenge.” The panel also suggested in a pair of parentheticals that the purported novelty of a missing claim limitation may inform a more substantive distinction:

We have not previously decided whether AAPA improperly forms the basis for a petition when it is used to show that a claim limitation (characterized by the patent as not disclosed in the prior art) would have been obvious over the prior art. That is not the case here, where CSI properly relied on general background knowledge to supply missing claim limitations (which Shockwave does not argue were novel to the invention) and used AAPA as evidence of that general background knowledge.

Because CSI had not unambiguously described the angioplasty balloon catheter AAPA as a “basis” for its challenges, and relied on the AAPA to provide conventional claim elements in its obviousness analysis, the Federal Circuit found the AAPA was properly relied on as evidence of background knowledge of the art. Among other things, the Court also found that the Board did not improperly discount objective indicia evidence directed to the “potential” commercial success of Shockwave’s product in development, and that CSI had standing to pursue its cross-appeal as to one upheld claim because it was close to beginning clinical trials of a product likely to be accused of infringement. Ultimately, the Court affirmed on all grounds raised in Shockwave’s appeal; reversed on CSI’s cross-appeal; and found all challenged claims of the ’371 patent to be unpatentable over the prior art.

The full opinion can be found here.

By Jason A. Wrubleski

Sign up